Stained glass dates back to at least the Roman Empire when craftsmen peddled wares including stained glass. The history of stained glass takes on legendary elements as the mixture of craftsmanship, science, art, and religion all blend into a divine tale of trial and error. It is metallic oxides that influence the creation of many hues during the manufacturing of stained glass.

The Lycurgus Cup, one of the most mysterious and famous relics of stained glass, seems to have formed by accident during its making. The cup is composed of dichroic glass, which changes color depending on the light. Lit from inside, the cup glows red, while outside light reveals an opaque green-colored hue. There are no other existing examples of such pieces from the Roman period. Scientists say it is the development of nanoparticles in the glass that is responsible for the drastic color change, and that a lack of control of the coloring process caused its development. Today it is housed in the British Museum.

Click here to see The Lycurgus Cup, 4th century CE

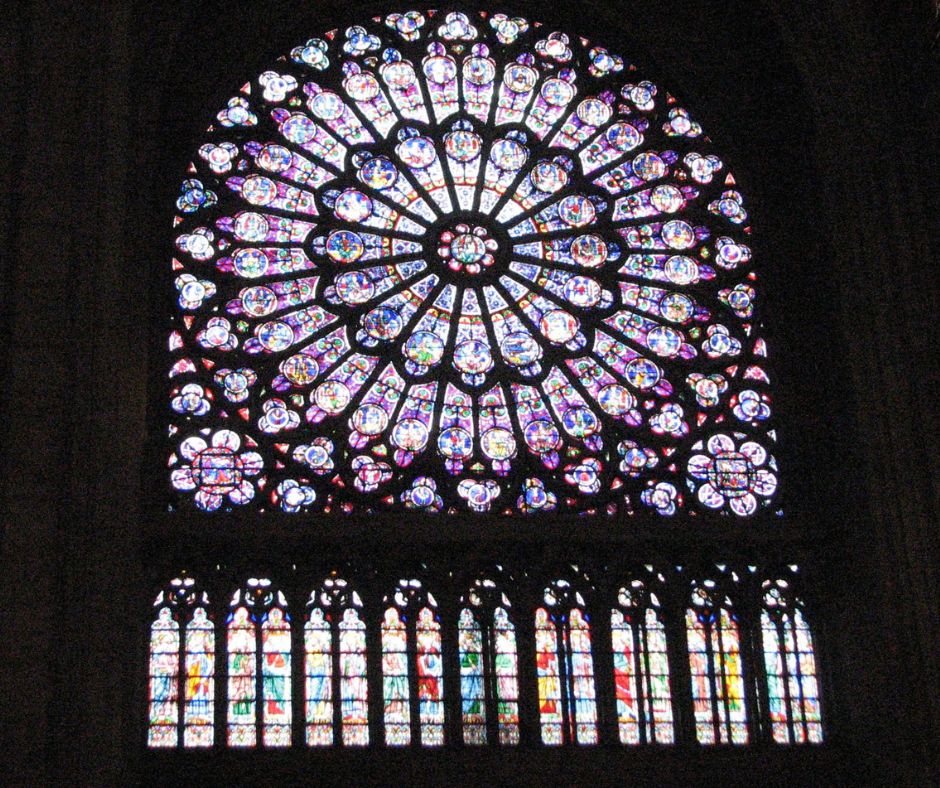

Stained glass windows were adopted into the atmosphere of medieval monasteries in the 7th century. Soon they could be found in cathedrals across Europe. The original designs were small, simple, and Romanesque. But by the 12th century, Gothic architecture replaced the predominant style with soaring spires and towering stained glass windows that bathed the interior in light. The near-Parisian Abbey of Saint-Denis personifies this gliding style; Abbot Suger rebuilt the abbey following the mystical principles of light.

Stained glass adorned Islamic mosques and palaces across the Middle East by the 8th century reflecting the rich ornate styles of Islamic architecture. The Book of the Hidden Pearl, written by Persian chemist Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, is a colored glass recipe book written about the craft.

The Renaissance and Reformation eras saw a shift in both technique and subject in stained glass windows, a transformation that helps to date pieces salvaged from bygone days. The mosaic style bound by thick lead casings vanished. Also, artists painted enamel directly on the glass before it was fired. Stained glass windows became more common in secular buildings and the homes of nobles, and featured more humanlike and earthy scenes than the previous divine and biblical renderings.

The fall in popularity of stained glass up to the 19th century was mostly due to Protestant Reformation and Counter-reformation, movements allergic to elaborate decoration. Glass workshops centered in the Lorraine region of Europe vanished after many palaces and castles were razed to the ground during the war.

Stained glass windows came back into popularity in America during the Gothic Revival when church congregations called for a return of the leaded art form. The revival occurred in designs for churches across Europe, as well, and stained glass windows were often incorporated into designs to replace glass destroyed during World War II. A sort of new renaissance was born.

Stained glass artists also reimagined technique and design in less cosmopolitan parts of the world. In Australia and New Zealand, those wealthy enough began importing stained glass from England. A feature of stained glass made by natives was the native plants and wildlife used in the design, but the 1930s Depression brought destitution to the native studios.

In South Africa, artist Paul Blomkamp used resin bonding and thin glass due to the impracticality of obtaining the lead. Italian Swiss craftsman Claudio Pellandi set up a studio in Mexico for leaded glass, etching, beveling, and silvering mirrors. Famous artist Marc Chagall designed stained glass for the chapel of the Hadassah hospital in Jerusalem.

By the 1960s, small craftsmen could make stained glass due to the invention of a small furnace for craftspeople. Hot glass became a course in colleges and universities. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Prairie Style” philosophy of architecture incorporated stained glass windows featuring geometric designs and abstract shots of color juxtaposed into clear glass.

Ever an art form, whether imbibed with symbolism or not, stained glass retains its beauty and collectibility throughout the centuries, even as new forms and techniques of expression transform this medium of expression.

Olde Good Things houses a number of fine stained glass windows reclaimed from historic places such as the Waldorf Astoria NYC, as well as altered antiques composed of the glass from the famous Robert Sowers window at JFK Airport.

Works Cited

“History of Stained Glass.” The Stained Glass Association of America, https://stainedglass.org/resources/history-of-stained-glass/. Accessed 27 July 2022.

LaChiusa, Chuck. “Reformation Stained Glass Windows.” Buffalo Architecture and History, https://buffaloah.com/a/DCTNRY/stained/renais.html. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Richman, Kelly. “Stained Glass History, from Ancient Art to Contemporary Installations.” My Modern Met, 28 April 2019, https://mymodernmet.com/stained-glass-history/. Accessed 27 July 2022.